The main ad that has annoyed me- sponsored on IG

Over the past couple of weeks, I’ve found myself (perhaps irrationally) annoyed at an ad campaign that has been EVERYWHERE. This seems to be a combination of my social media algorithm showing it to me and the fact that I see the physical posters on every tube journey I take.

It’s the new Imperial War Museum ad campaign which focuses on their fashion collections.

Part of me feels like- Liz its museums- don’t be so angry about it- they are your happy place! But at the same time, this campaign has really frustrated me.

Physical poster at Canada Water

The other two ads from the series at Stratford station

So why does it annoy me so much? Ah where to begin…

trivialises fashion history

makes a joke out of a very serious fear and horrific wartime experiences

it’s confusing from an audience/visitor engagement pov

its messaging doesn’t make sense

the images are at weird angles

All in all, it’s a poorly thought-out campaign that feels like it was created by an ad agency with little input from museum professionals (n.b. I haven’t been able to find out which ad agency are behind the campaign)

I’m going to break down why I have issues with each of these ads- focusing on the first one I saw (the sustainable fashion one). These speak to me of the idea that fashion sells, and any museum that has a fashion collection sees it as a marketing tool, without perhaps fully appreciating the far richer stories that garments can tell beyond “look, cool old clothes!”.

One thing to note is that the physical ads do give you a collection number and a tiny amount of information about the object within the image, while the online ones don’t.

So first off, the ‘lucky’ underwear. Seen in this image is an early twentieth-century camisole. The IWM website states of this object:

Camisole worn by Mrs Margaret Gwyer, a survivor of the sinking of the RMS Lusitania, which was torpedoed by the U20 on 7 May 1915. Mrs Gwyer fell into the water from a lifeboat and was sucked into one of the sinking ship's funnels. However, the explosion of one of the ship's boilers blew her back to the surface, where she was picked up and later reunited with her husband. She kept the oil-stained camisole as a reminder of her ordeal.

So, this can, in some ways, be seen as ‘lucky underwear,’ but the ad lacks any real context. When I started looking into this garment, I found that IWM had also used the camisole for a previous campaign in 2014.

The images below come from a blog called World War Zoo Gardens. You can read their full blog post on the original ‘lucky underwear’ campaign here.

For me, the original campaign is far more impactful and also respectful of the object. It tells (in some detail!) the object's story and quite effectively anthropomorphises the camisole. I feel like this kind of text-heavy campaign would be seen as quite unfashionable now (too much to read, audience engagement issues, etc.). However, it is far more persuasive, I think, in encouraging the visitor to actually visit the IWM—which is surely the ultimate aim of any museum campaign.

I’m also interested in how the object itself is presented in these two campaigns.

The image used in the 2014 campaign

The image used in the 2025 campaign

Whilst I’m sure the garment hasn’t been cleaned up (its dirt is part of its story, after all!), there’s something about the 2025 images that present the camisole in a more sanitised manner. It looks cleaner and less dishevelled. While mounting it for the more recent image attempts to give the impression of the body underneath,, it loses some of its potency as an object because it appears to float.

Moving on to the advertising poster featuring the gas mask bag. Whilst it could be argued that the camisole WAS lucky underwear, calling a gas mask bag an ‘it bag’ feels quite crass. The bag was made by Waldybag a Jewish-owned (important given the context of this being made during WW2) British high-end handbag brand founded in London in 1915. This particular gas mask bag was owned by Lady Stella Reading and her initials are attached to its glossy leather front.

The IWM website describes the bag as follows:

Although issued in standard container made of rigid card with a carrying string, private purchase containers could be as elegant and discreetly exclusive as the owner could afford. This example stows the respirator within the base of the handbag, permitting conventional use of the accessory as well as easy access to the mask if required in a hurry.

Most people carried a gas mask for fear of possible gas attacks by the enemy. Lady Reading chose to carry hers in a customised bag which had much akin with the general fashionable shapes of handbags at the time. However calling it an ‘it’ bag, diminishes the very real and frightening experiences of living through war.

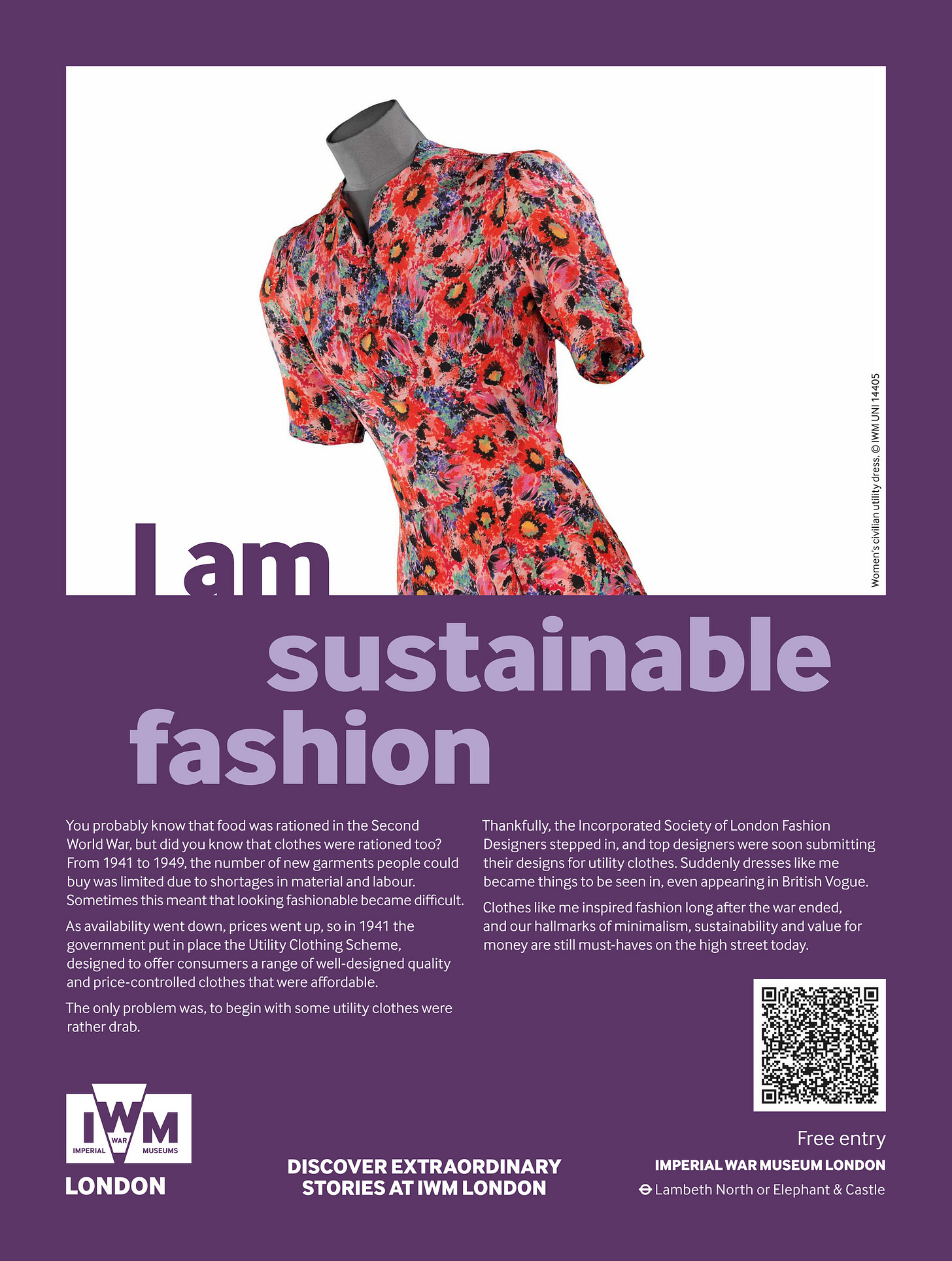

And finally onto the ad I draw biggest issue with. The ‘I am sustainable fashion’ advertisement (you can find the dress on IWM’s website here)

The dress seen is a CC41 labeled dress made from rayon. As there isn’t a picture of the label online I can’t be precisely sure of the date- but given the context of the ad, I would assume this is a wartime piece, rather than a CC41 piece produced after the war.

I have problems with this one on many levels- but perhaps one of the most glaring is the ‘audience’ confusion this has created.

I’ve had this ad ‘sponsored’ to me three times on facebook (I think the ads are different as each has had different comments underneath it). In each instance there were confused commenters thinking these ads were for a new IWM exhibition focusing on sustainable fashion. Or, relatedly, VERY angry commenters reflecting on the closure of the Lord Ashcroft Gallery at IWM in June 2025, to make way for post-WW2 galleries.

There isn’t a sustainable fashion exhibition happening at IWM, and the last fashion exhibition they hosted was ‘Fashion on the Ration’ back in 2015. This confusion stretched beyond facebook and I forced myself through a GB News segment where Nigel Farage discussed the closure of the Lord Ashcroft Gallery with medal dealer Pierce Noonan (I have linked the video here, but honestly I feel like I’ve watched this so you don’t have to :/). Farage asks Noonan, ‘ are you aware there’s going to be an imperial war museum display about sustainable fashion?’ to which he… quite mysteriously seeing as there isn’t one… replies ‘I am aware of that’. I know GB News spouts bile most of the time, but still, this demonstrates the confusion the campaign has caused. As an aside, if you are interested in the IWM’s 2025 programme, I’ve linked it here.

In some ways, the digital confusion has been exacerbated by the QR code. When I clicked on it, I was expecting to be taken through to a ‘discover the collection’ style landing page where you might be able to find out more about these interesting garments in their collection. However, instead it just takes you through to the home page for the website.

The wording of this advertisement and the choice of garment, is also problematic. Some of my recent academic research has focused on how we might use fashion history to inspire new models of more sustainable fashion (from production through to consumption). In doing this research, I’ve found that, repeatedly, fashion in WWII is held up as an ‘example’ of how we might learn from the past in order to live more sustainably. It’s problematic, however, to simply conflate wartime restrictions with concepts of ‘sustainability’. Bethan Bide deals with this better than I can in a short substack post, so I suggest that you read her article Learning from the Past: Why the Second World War 'Make Do and Mend' Scheme Provides a Poor Model for the Future of Sustainable Fashion

I did also discover another version of the ad, I found this digitally but it appeared in print, in the BBC history magazine. This, in format, is quite similar to the ‘lucky underwear’ ads of 10+ years ago and offers some more background on the dress and what it stands for (thinking about the audience- the reader of BBC History is far more likely to engage with a text-heavy ad). However, again, it has elements I draw issue with. The first two paragraphs are fine, but it goes downhill from there. The IncSoc collection mentioned here, whilst praised by Vogue (and acquired by the V&A) was not commercially successful and many manufacturers were resentful that IncSoc dictated the designs they should produce- particularly as most of IncSoc’s designers had limited understanding of how the ready-to-wear industry worked. The language of the advertisement here suggesting ‘thankfully’ they stepped in, implies the ready-to-wear industry was floundering without them- but this wasn’t the case and presents an erroneous top-down impression of the British fashion industry (pre-war ready-to-wear firms were generally taking their couture inspiration from Europe, not Britain). The dress seen in the advert is not in any way representative of the garments produced by IncSoc as ‘models’ for the Utility scheme; it actually is much more akin to late 1930 American ready-to-wear, which was where lots of British firms were increasingly turning for inspiration, particularly when it came to day dresses.

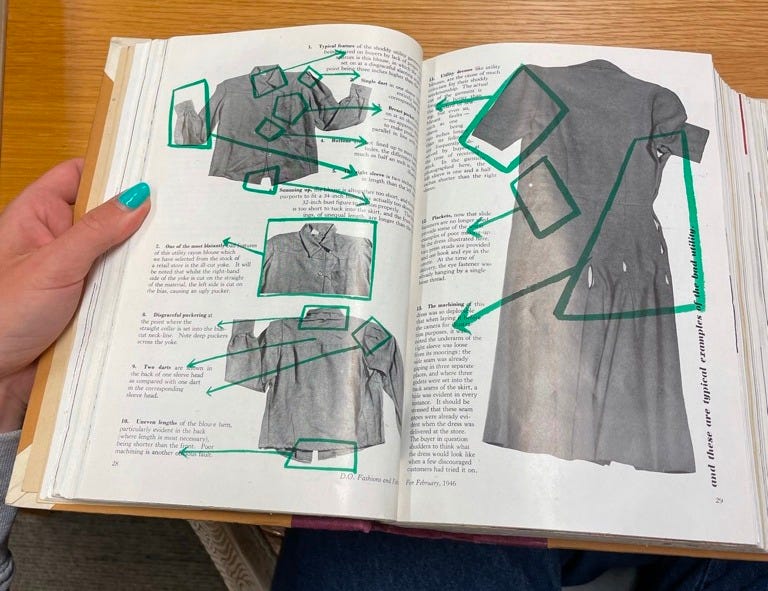

Today we tend to think of sustainable fashion as representing small-scale ‘slow’ high-quality production (I’d really love to know how the ad company behind the campaign were defining it). But Utility was very different- manufacturers had to offer production runs of at least 1000 garments, and this, in turn, meant it was mostly sizeable businesses who were part of the scheme. These companies focused on fast, efficient production using modern machinery. Garments were supposed to meet ‘minimum standards’ which did mean that the CC41 label came to be seen as a marker of quality. However, this wasn’t universal, and there’s several examples in the trade press where journalists bemoan the poor quality of Utility garments.

The Utility scheme did help to improve the quality and standardisation of mass produced clothing. However, as Bethan states in her article which I linked to above, ‘despite the proven efficacy of mass government regulation at reducing fashion consumption, it is not considered a realistic solution to create a more sustainable fashion industry today.’

I feel I’ve perhaps said enough, but I’d love to know what anyone else whose seen this campaign thought of it?